MUST READ

Is God Using COVID 19 to smash Russia’s orthodox pagan Christianity? Russian Evangelicals Penalized Most Under Anti-Evangelism Law : Russia's Newest Law: No Evangelizing Outside of Church

Putin and the Russian Orthodox church as the Pharaoh that must let God’s people in Russia Go: Why Russians Are Getting Sick of Church?

Why Russia is afraid of Jehovah’s Witnesses?

On Monday, July 17, the Russian Supreme Court rejected an appeal of an earlier ruling sanctioning Jehovah’s Witnesses as an extremist group. As a last ditch effort, Russian Jehovah’s Witnesses intend to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights. But, as of now, Jehovah’s Witness gatherings and preaching are criminal offenses in Russia. The Russian government also has the legal authority to liquidate any property held by Jehovah’s Witnesses as an organization.

There are over eight million Jehovah’s Witnesses in 240 countries worldwide. Russia, with a population of more than 150 million, has a total of 117,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses – one Jehovah’s Witness per 850 people.

Who are Jehovah’s Witnesses, and why would the Russian, or any, government consider them to be a threat?

Early history

The story of Jehovah’s Witnesses begins in the late 19th century near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with a group of students studying the Bible. The group was led by Charles Taze Russell, a religious seeker from a Presbyterian background. These students understood “Jehovah,” a version of the Hebrew “Yaweh,” to be the name of God the Father himself.Russell and his followers looked forward to Jesus Christ establishing a “millennium” or a thousand-year period of peace on Earth. This “Golden Age” would see the Earth transformed to its original purity, with a “righteous” social system that would not have poverty or inequality.

Russell died in 1916 without witnessing the return of Jesus Christ.

But his group endured and grew. The name “Jehovah’s Witnesses” was formally adopted in the 1930s.

Early Jehovah’s Witnesses believed 1914 to be the beginning of the end of worldly governments that would culminate with the Battle of Armageddon. Armageddon specifically refers to Mount Megiddo in Israel where some Christians believe the final conflict between good and evil will take place. Jehovah’s Witnesses, however, expected that the Battle of Armageddon would be worldwide with Jesus leading a “heavenly army” to defeat the enemies of God.

They also believed that after Armageddon, Jesus would rule the world from heaven with 144,000 “faithful Christians,” as specified in the Book of Revelation. Other faithful Christians would be reunited with dead loved ones and live on a renewed Earth.

Over the years, Jehovah’s Witnesses have reinterpreted elements of this timeline and have abandoned setting specific dates for the return of Jesus Christ. But they still look forward to the Golden Age that Russell and his Bible students expected.

Given the group’s belief in a literal thousand-year earthly reign of Christ, scholars of religion classify Jehovah’s Witnesses as a “millennarian movement.”

What are their beliefs?

Jehovah’s Witnesses deny the Trinity. For most Christians, God is a union of three persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit.Instead, Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that Jesus is distinct from God – not united as one person with him. The “Holy Spirit,” then, refers to God’s active power. Such doctrines distinguish Jehovah’s Witnesses from mainline Christian denominations, all of which hold that God is “triune” in nature.

Their biblical interpretations and missionary work certainly have critics. But it is the political neutrality of the group that has attracted the most suspicion.

Jehovah’s Witnesses accept the legitimate authority of government in many matters. For example, they pay taxes, following Jesus’ admonition in Mark 12:17 “to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.”

But they do not vote in elections, serve in the military or salute the flag. Such acts, they believe, compromise their primary loyalty to God.

A history of persecution

Jehovah’s Witnesses have no political affiliations, and they renounce violence. However, they make an easy target for governments looking for internal enemies, as they refuse to bow down to government symbols. Many nationalists call them “enemies of the state.”As a result, they have often suffered persecution throughout history in many parts of the world.

Jehovah’s Witnesses were jailed as draft evaders in the U.S. during both world wars. In a Supreme Court ruling in 1940, school districts were allowed to expel Jehovah’s Witnesses who refused to salute the American flag. Through subsequent legal battles in the 1940s and 1950s, Jehovah Witnesses helped expand safeguards for religious liberty and freedom of conscience both in the United States and Europe.

In Nazi Germany, Jehovah’s Witnesses were killed in concentration camps; a purple triangle was used by the Nazis to mark them. In the 1960s and ‘70’s, scores of African Jehovah’s Witnesses were slaughtered by members of The Youth League of the Malawi Congress Party for refusing to support dictator Hastings Banda. Many Witnesses fled to neighboring Mozambique, where they were held in internment camps.

Now it is Russia.

But given their commitment to God above all things, Jehovah’s Witnesses see themselves as being persecuted by those who value loyalty to country over any other principle. They also believe that the Russian government has “trampled on the guarantees of their own laws.”

Many Jehovah’s Witnesses still attach a great importance to dates. Many Jehovah’s Witnesses are filled with foreboding, as April 20, the day the Russian Supreme Court first ruled against them, is also the birthday of Adolf Hitler.

Their memories of persecution have not faded with time.

'We Liked to Sing. Now We Can Only Whisper.' How Russia Is Stepping Up Its Persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses sing songs at the beginning of a meeting in Rostov-on-Don on Nov. 13, 2015.

Alexander Aksakov—For The Washington Post via Getty Images

On a chilly November

weeknight in a drab apartment building in outer Moscow, seven adults and

two small children crowded around a computer screen and sang a hymn as

quietly as they could. “Whatever test may come your way, never yield to

doubt or fear. Jehovah will provide escape, our God ever will be near!”

they chorused.

“At the kingdom hall we liked to sing loudly, but now we can only whisper,” said Yevgeny, who asked his last name be withheld to avoid arrest. “If anything happens, we’re just watching movies with friends.”

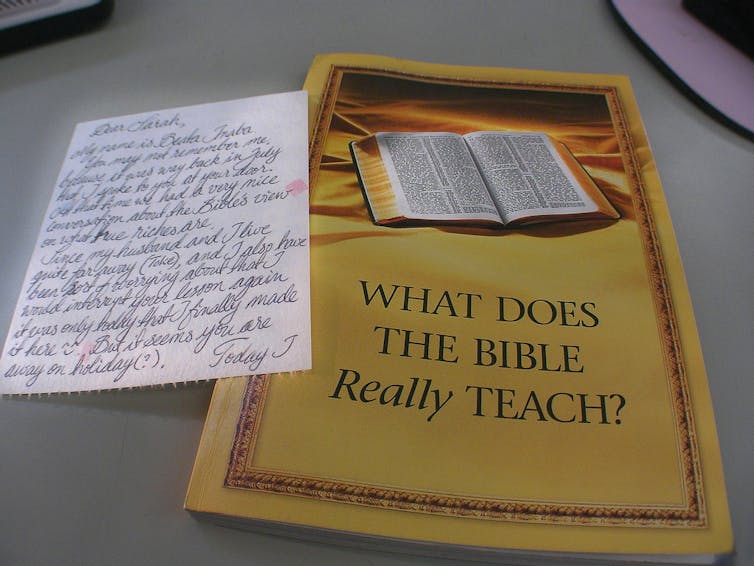

Jehovah’s Witnesses, a U.S.-based international Christian denomination claiming 8.5 million members, are a common sight in countries around the world, as proselytizing door-to-door is a central tenet of their faith. But in Russia they have been forced underground following imprisonment and allegations of torture; only Islamic fundamentalists are treated more harshly.

Russia’s justice ministry calls the group, which has grown its membership here to 170,000, a threat to public order. They were banned as “extremist” in Russia in 2017, putting them in the same ranks as neo-Nazis. A spokesperson for the conservative Russian Orthodox Church, which has grown in influence under Putin, has said Jehovah’s Witnesses manipulate people’s consciousness and “can not be called Christians.”

“At the kingdom hall we liked to sing loudly, but now we can only whisper,” said Yevgeny, who asked his last name be withheld to avoid arrest. “If anything happens, we’re just watching movies with friends.”

Jehovah’s Witnesses, a U.S.-based international Christian denomination claiming 8.5 million members, are a common sight in countries around the world, as proselytizing door-to-door is a central tenet of their faith. But in Russia they have been forced underground following imprisonment and allegations of torture; only Islamic fundamentalists are treated more harshly.

Russia’s justice ministry calls the group, which has grown its membership here to 170,000, a threat to public order. They were banned as “extremist” in Russia in 2017, putting them in the same ranks as neo-Nazis. A spokesperson for the conservative Russian Orthodox Church, which has grown in influence under Putin, has said Jehovah’s Witnesses manipulate people’s consciousness and “can not be called Christians.”

“We can’t talk about any sort of justice here,” Tatyana Alushkina told TIME. “This is persecution of the Jehovah’s Witness religion.”

“It’s so difficult for him, but that’s the path of a Christian, and we chose it ourselves,” said Yevgeny, an old friend of Alushkin’s. “We don’t want to sit in prison, but neither did Daniel want to go in the lion’s den.”

Authorities in the U.S. have raised concerns about the worsening treatment of Jehovah’s Witnesses, which comes as Moscow is locked in a geopolitical standoff with Washington. Former Kansas senator Sam Brownback, who now serves as the U.S. ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, told TIME Alushkin’s conviction was part of a wave of “very aggressive” persecution that led his office to add Russia to its special watch list last year. “You may agree or disagree with their ideology, but they are peaceful practitioners of faith and they are entitled to practice their faith,” Brownback said.

With roots in a 19th century Bible studies movement in Pennsylvania, Jehovah’s Witnesses are known for a literal interpretation of the Bible as defined by a small council of elders in Warwick, New York, and view earthly governments as controlled by the devil. They believe that Armageddon is imminent and that God’s kingdom will soon be established on earth.

While they have the most “publishers,” or active members, in the United States, Mexico, Brazil and Nigeria, Russia is one of their largest congregations in Europe.

After the 2017 ban, 395 branches of the church in Russia were shut down and their evangelizing and meetings were forbidden. Believers have been forced to gather secretly in apartments, reading prayers and discussing the bible with half a dozen other small groups via video link. Each session starts with an admonition to make sure the door is closed in case someone tips off the police.

The organization says 297 members in Russia are facing criminal charges; 43 are in detention and 22 are under house arrest. At least 5,000 have fled Russia for Europe and North America.

In February, a court in Oryol sentenced Dennis Christensen, a Danish Jehovah’s Witness elder who lived in the country since 2000 and has a Russian wife, to six years in prison. Elder Sergei Klimov in Tomsk was similarly sentenced six years, and six men in Saratov were given terms ranging from two to three-and-a-half years in September

That same month, the State Department placed a U.S. travel ban on two Russian officials for allegedly torturing seven Jehovah’s Witnesses in the Siberian oil town of Surgut. The believers said law enforcement agents had beaten them, administered electric shocks and suffocated them with plastic bags during interrogations. Criminal charges have been brought against four men, and another 17 people are considered suspects, one of them, legal consultant Timofei Zhukov, told TIME.

As part of raids on more than 20 apartments in July, masked agents climbed in through the balcony at 6:20am and tied Zhukov up on the floor, after which one kicked him in the head “as if he was kicking a football,” he said. He says he was held at the investigators’ office for hours as screams echoed down the hall.

“When peaceful people are tortured, it’s fascism,” Zhukov said. “They physical and morally humiliate people so they will deny their faith.”

The brutal repressions have reminded some in the church of when Joseph Stalin sent nearly 10,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses to guarded settlements in Siberia. “For now we don’t have hundreds of people in camps, we don’t have deportation,” said spokesman Yaroslav Sivulskiy. “But we hadn’t heard of torture like in Surgut, how people in masks threw even old people to the ground.”

Sivulskiy spent a year and a half in Soviet prisons for refusing army conscription, a principle that still brings Jehovah’s Witnesses into conflict with the Russian authorities today, as does their opposition to blood transfusions.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has been ambivalent about the ban. Asked about it last year, he said Russia could be “more liberal toward representatives of different religious sects, but shouldn’t forget” that 90 percent of people here consider themselves Orthodox. (Polling suggests the actual number is closer to 75 percent.)

Once a source of support for the tsars, the resurgent Orthodox church has now become a pillar of Putin’s rule, which Patriarch Kirill has described as a “miracle of God,” and of Russian influence abroad. The state gives tens of millions of dollars to the church each year, and the military is building a 300-foot-tall Orthodox cathedral with steps made of melted down Nazi tanks at a patriotic park outside Moscow.

Jehovah’s Witnesses oppose such cozy relations with the state. They do not vote or hold public office, and unlike the Seventh Day Adventist or Pentecostal churches, they have not participated in Putin’s council for cooperation with religious associations. “They try to avoid talking with the government, they don’t participate in councils, they don’t go anywhere, they pay taxes and register and that’s it, and our government is suspicious of this,” said Alexander Verkhovsky, who tracks racial and religious discrimination at Moscow’s SOVA Center.

While the Russian authorities continue to tighten the screws, each arrest only convinces Jehovah’s Witnesses that they are in the right. “Christ said they will persecute you for your faith,” Zhukov said, “and when you see it with your own eyes, you’re even more convinced.”