Brutal monk made saint of California

http://ivarfjeld.com/2015/09/24/brutal-munk-made-saint-of-california/

Thinker is Professor of American Indian Cultures and Religious Traditions at Iliff School of Theology and author of Missionary Conquest: The Gospel and Native American Genocide.

Thinker reacts to the canonization of Junipero Serra done by Pope Francis during the present visit to the US. Thinker recalled the “almost slave-labor conditions” that Native Americans were subjected to under Serra’s leadership.

Credited with baptizing around 90,000 Indians during his lifetime, there is wide agreement among historians that Serra’s evangelism tactics were harsh by any modern standard.

“The army would round the person up, bring him back to the mission compound, and then the person is punished,” he said, “The mission compound was run kind of like a military boot camp.”

A group of Native Americans remains opposed to the canonization. They prayed at the mission’s cemetery and to express disappointment that the pope ignored a request to listen to them. “Supposedly as a man of God that he doesn’t care what thousands of California Indians are saying, even to come and meet with us,” Esselen Nation Tribal Chairwoman Louise Miranda Ramirez said.

“Serra was not the face of evil”, says Deborah Miranda, a professor of literature at Washington and Lee University and an Ohlone Costanoan Esselen Indian. “But there were so many atrocities happening and he closed his eyes,” she said. “I don’t think he should be rewarded for that.”

My comment:

Lets keep the unbiblical canonization process of the Roman Catholic Church for a moment. And rather focus on the injustice done to people who were forcefully converted to Catholicism druing the failed Spanish conquest of California.

To canonize a brutal oppressor of the Spanish colonialism is yet another example of the double talk of the present Pope. He speaks against Capitalism and oppression of the poor in one TV-camera. And in the next, he praises Franciscan monk Junipero Serra.

A lot of people do not mind that the Christian faith is defamed by the Pope. They use the papacy as an example of why they do not believe in the Biblical faith in Jesus.

Have nothing to do with the fruitless deeds of darkness, but rather expose them.

May Jesus the Messiah have mercy on all deceived souls.

Written by Ivar

Junípero Serra's brutal story in spotlight as pope prepares for canonisation

Many have condemned decision to elevate 18th-century missionary to

sainthood after violence suffered by Native Americans he was said to be

protecting

Astatue of Junípero Serra stands outside the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel in San Gabriel, California.

Photograph: Mario Anzuoni/Reuters

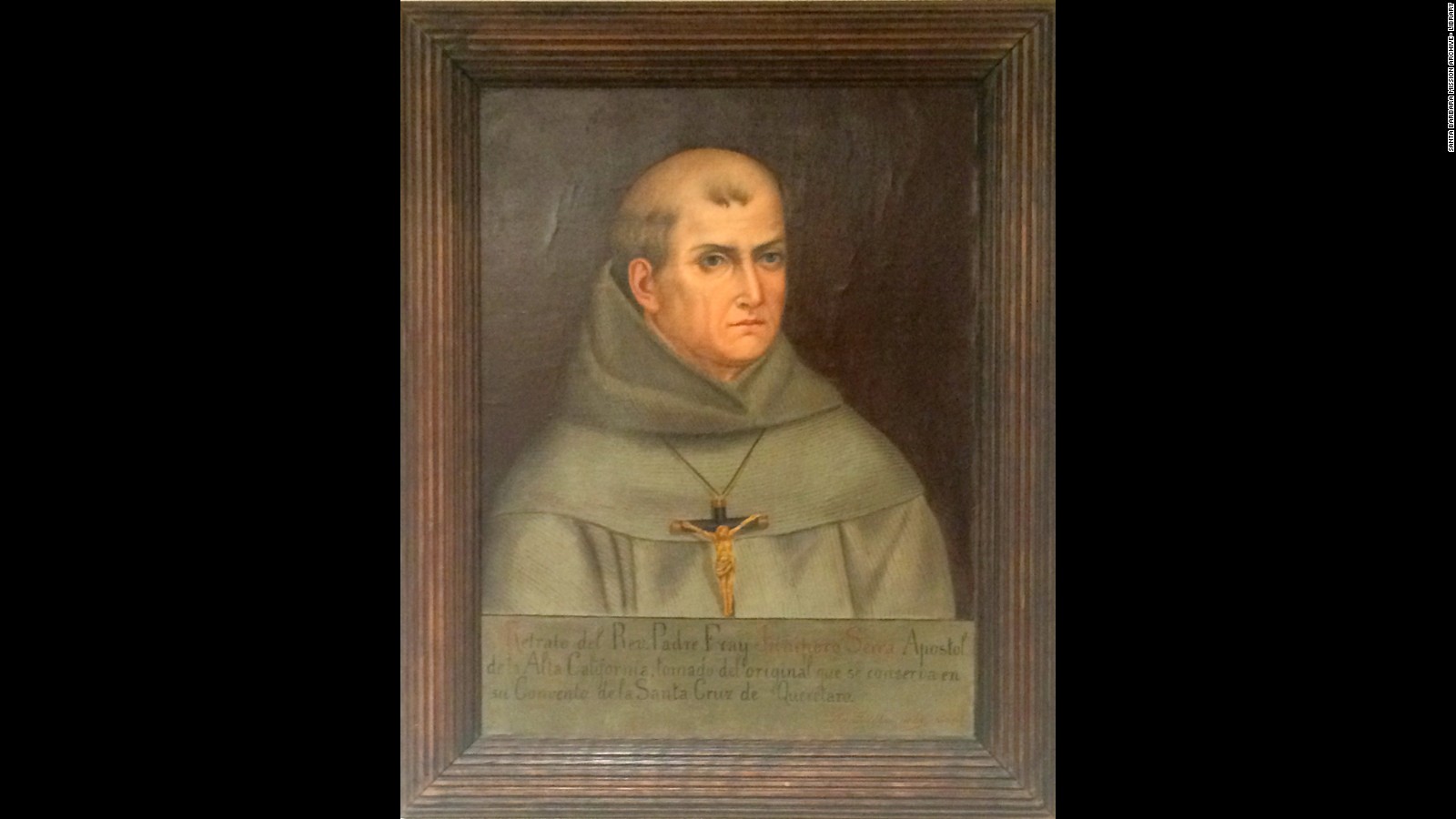

Generations of American schoolchildren have been taught to think

of Father Junípero Serra as California’s benevolent founding father, a

humble Franciscan monk who left a life of comfort and plenty on the

island of Mallorca to travel to the farthest reaches of the New World

and protect the natives from the worst abuses of the Spanish imperial

army.

Under Serra’s leadership, tens of thousands of Native Americans across Alta California, as the region was then known, were absorbed into Catholic missions – places said by one particularly rapturous myth-maker in the 19th century to be filled with “song, laughter, good food, beautiful languor, and mystical adoration of the Christ”.

What this rosy-eyed view omits is that these natives were brutalized – beaten, pressed into forced labour and infected with diseases to which they had no resistance – and the attempt to integrate them into the empire was a miserable failure. The journalist and historian Carey McWilliams wrote almost 70 years ago the missions could be better conceived as “a series of picturesque charnel houses”.

Little wonder, then, that Pope Francis’s decision to elevate Serra to sainthood during his visit to Washington this week has revived longstanding controversies and enraged representatives of California’s last surviving Native American populations. There have been protests outside some of California’s most heavily visited Missions, petitions, open letters written both to the pope and to California’s political leaders, and even an attempt by members of the state legislature to have Serra replaced as one of California’s two representative figures in Washington’s National Statuary Hall. Natives travelled to California and Washington this week to protest against Serra’s elevation in person.

Opponents point out that, from the time Serra arrived in 1769, the native population was ravaged by European diseases, including syphilis spread by marauding Spanish soldiers. Indians brought into the missions were not allowed to leave, and if they tried they were shackled and severely beaten.

They were used as forced labour to build out the Mission’s farming projects. They were fed atrociously, separated from close family members and packed into tight living quarters that often became miasmas of disease and death.

When the Native Americans rebelled, which they did on at least two occasions, their rebellions were put down in brutal fashion. When Native American women were caught trying to abort babies conceived through rape, the mission fathers had them beaten for days on end, clamped them in irons, had their heads shaved and forced them to stand at the church altar every Sunday carrying a painted wooden child in their arms.

Passions are riding high on both sides. While Serra’s critics say he was responsible for the near-eradication of California’s native peoples, the state’s governor, Jerry Brown, has defended him as “a very courageous man”, an innovator and a pioneer, and vowed that his statue will stay in Washington “until the end of time”.

In many ways, the issue is reminiscent of the Vatican’s campaign a few years ago to canonise Pius XII, the wartime pope accused in many quarters of failing to stand up to the Nazis and helping in their rise to power, but defended in others as a holy man who did his part to save many hundreds of thousands of Jews.

The push to canonise Pius XII (now on hold) came in the wake of a 1998 papal document that sought to atone for the church’s silence in the face of the Holocaust. Likewise, Serra’s sainthood follows an apology issued by Pope Francis in Bolivia this summer for the “grave sins … committed against the native peoples of America in the name of God”.

That, however, has only further raised the hackles of Serra critics, who say the apology means nothing if the Vatican simultaneously seeks to canonise a person exemplifying the actions for which the apology was issued. “Apologies that aren’t followed by a change of behaviour, in general, don’t carry a lot of weight,” Deborah Miranda of Washington and Lee University, who is of California Native American descent, said in a recent magazine interview.

Even mainstream Catholics have been surprised that Pope Francis has championed Serra without going through the usual four-step review process, including verification of two miracles. Serra has been credited with only one.

The cause of his sainthood, which was first proposed in 1930, was long ago assumed to have stalled because of the controversies surrounding his legacy.

But Francis, as the first Latin American pope, has an obvious interest in creating a role model for Latinos in the United States and the rest of the American continent – an interest echoed by the state of California, which can now look forward to a global wave of Serra-related tourism. The pope also appears to have an interesting theological take on Serra’s imperfections. Kevin Starr, widely regarded as California’s pre-eminent state historian, summarised the Vatican’s view this way: “Saints do not have to be perfect. Nobody is perfect. Sanctity is just another mode of imperfection.”

In other words, it is enough to state that the good outweighs the bad. José Gómez, the first Latino archbishop of Los Angeles and an enthusiastic Serra champion, wrote recently: “Whatever human faults he may have had and whatever mistakes he may have made, there is no questioning that he lived a life of sacrifice and self-denial.”

Gómez also argued that we cannot judge 18th-century behaviour by 21st-century standards – a form of historical relativism that the Serra critics find particularly galling. John Cornwell, a British journalist turned academic who has written extensively about the Vatican, including an acclaimed book about Pius XII, said the argument also clouded the important question of whether Serra was an appropriate exemplar for today’s faithful.

“For those who argue that we should not judge the values of the past by those of the present,” Cornwell told the Guardian, “one could, and should, object that it’s important to learn the lessons of history.”

To Native Americans like Valentin Lopez, the chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band based in Sacramento, those lessons are not complicated. Serra, in his view, was part of a colonial enterprise whose goal was the complete subjugation of California’s native peoples. The mission system he set up was based on coercion, punishment and indifference to Indian suffering, against which his expressions of piety were no more than window-dressing.

“It’s amazing to me this is even a debate,” Lopez told the Guardian. “There is no debate – it’s like debating the pros and cons of the genocide of the Jewish people in world war two. The only reason this is not treated as a black and white issue is because of the lies that the church and the state of California have perpetuated from the time of the missions.”

Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1884 bestselling novel Ramona set the tone for a mythologised history of the Missions, giving the impression Spanish colonialism had been an idyll for settlers and Native Americans alike and that the natives only suffered after the gringos began arriving. Even the most ardent Catholic historians now accept this is flat-out wrong.

A flurry of recent Serra scholarship, however, suggests the politics of the Spanish conquest were complicated. Missions were established with much greater success and lesser suffering in other parts of the American continent – particularly by the Jesuits. Serra’s mandate only arose because the Vatican temporarily disbanded the Jesuits in 1767, and many of the mistakes he and the Franciscans made were the result of inexperience, according to Professor Starr.

“The perspective of Franciscans and Dominicans of that era was: God will punish us for the way we treat the Indians, so we’ve got to protect them as some kind of atonement,” Starr told the Guardian. “Serra knew he couldn’t keep California a Franciscan mission protectorate forever. He hoped that by the time Spaniards came in large numbers, Native Americans would be educated and competent to deal with it. That was the dream, but the dream never came true.”

The biggest philosophical divide among serious historians is whether Serra’s initiative was worth undertaking in the first place. Catholic scholars – including Professor Starr – tend to take an indulgent view of the church’s evangelizing mission, while Native American advocates like Lopez view the imposition of Catholicism as a violation of the Indians’ longstanding spiritual traditions, just as the Spanish conquest disrupted and violated their way of life more generally.

The Vatican would like to believe that Serra and the missionaries were somehow separate from the Spanish colonial enterprise, and that the army’s abuses should not in any way be laid at Serra’s door. Pope Francis said in May that Serra was one of a generation of missionaries “who … defended the indigenous peoples against abuses by the colonisers”.

Most historians, however, dismiss that interpretation as fanciful. While it’s true that Serra was often at odds with military commanders in the region, he travelled to the New World at the behest and direction of the same Spanish crown in command of the army. He couldn’t be against the colonisers, because he was one himself.

“The church and the army were partners,” Lopez said. “Junípero Serra’s own handwriting details the cruelties. His policy was to enslave the Indians – he didn’t let them leave the missions. You can’t blame that on Spanish soldiers.”

Out of deference to the papal visit, the push to have Serra’s statue in Washington replaced with the late astronaut Sally Ride – championed by LGBT advocacy groups as well as fans of space exploration – has been deferred until after Francis is back in Rome. But the sponsors of the measure, including a Latino state senator from Los Angeles and the speaker of the state assembly, have vowed to reintroduce it thereafter – paving the way for yet more showdowns over Serra in the foreseeable future.

Under Serra’s leadership, tens of thousands of Native Americans across Alta California, as the region was then known, were absorbed into Catholic missions – places said by one particularly rapturous myth-maker in the 19th century to be filled with “song, laughter, good food, beautiful languor, and mystical adoration of the Christ”.

What this rosy-eyed view omits is that these natives were brutalized – beaten, pressed into forced labour and infected with diseases to which they had no resistance – and the attempt to integrate them into the empire was a miserable failure. The journalist and historian Carey McWilliams wrote almost 70 years ago the missions could be better conceived as “a series of picturesque charnel houses”.

Little wonder, then, that Pope Francis’s decision to elevate Serra to sainthood during his visit to Washington this week has revived longstanding controversies and enraged representatives of California’s last surviving Native American populations. There have been protests outside some of California’s most heavily visited Missions, petitions, open letters written both to the pope and to California’s political leaders, and even an attempt by members of the state legislature to have Serra replaced as one of California’s two representative figures in Washington’s National Statuary Hall. Natives travelled to California and Washington this week to protest against Serra’s elevation in person.

Opponents point out that, from the time Serra arrived in 1769, the native population was ravaged by European diseases, including syphilis spread by marauding Spanish soldiers. Indians brought into the missions were not allowed to leave, and if they tried they were shackled and severely beaten.

They were used as forced labour to build out the Mission’s farming projects. They were fed atrociously, separated from close family members and packed into tight living quarters that often became miasmas of disease and death.

When the Native Americans rebelled, which they did on at least two occasions, their rebellions were put down in brutal fashion. When Native American women were caught trying to abort babies conceived through rape, the mission fathers had them beaten for days on end, clamped them in irons, had their heads shaved and forced them to stand at the church altar every Sunday carrying a painted wooden child in their arms.

Passions are riding high on both sides. While Serra’s critics say he was responsible for the near-eradication of California’s native peoples, the state’s governor, Jerry Brown, has defended him as “a very courageous man”, an innovator and a pioneer, and vowed that his statue will stay in Washington “until the end of time”.

In many ways, the issue is reminiscent of the Vatican’s campaign a few years ago to canonise Pius XII, the wartime pope accused in many quarters of failing to stand up to the Nazis and helping in their rise to power, but defended in others as a holy man who did his part to save many hundreds of thousands of Jews.

The push to canonise Pius XII (now on hold) came in the wake of a 1998 papal document that sought to atone for the church’s silence in the face of the Holocaust. Likewise, Serra’s sainthood follows an apology issued by Pope Francis in Bolivia this summer for the “grave sins … committed against the native peoples of America in the name of God”.

That, however, has only further raised the hackles of Serra critics, who say the apology means nothing if the Vatican simultaneously seeks to canonise a person exemplifying the actions for which the apology was issued. “Apologies that aren’t followed by a change of behaviour, in general, don’t carry a lot of weight,” Deborah Miranda of Washington and Lee University, who is of California Native American descent, said in a recent magazine interview.

Even mainstream Catholics have been surprised that Pope Francis has championed Serra without going through the usual four-step review process, including verification of two miracles. Serra has been credited with only one.

The cause of his sainthood, which was first proposed in 1930, was long ago assumed to have stalled because of the controversies surrounding his legacy.

But Francis, as the first Latin American pope, has an obvious interest in creating a role model for Latinos in the United States and the rest of the American continent – an interest echoed by the state of California, which can now look forward to a global wave of Serra-related tourism. The pope also appears to have an interesting theological take on Serra’s imperfections. Kevin Starr, widely regarded as California’s pre-eminent state historian, summarised the Vatican’s view this way: “Saints do not have to be perfect. Nobody is perfect. Sanctity is just another mode of imperfection.”

In other words, it is enough to state that the good outweighs the bad. José Gómez, the first Latino archbishop of Los Angeles and an enthusiastic Serra champion, wrote recently: “Whatever human faults he may have had and whatever mistakes he may have made, there is no questioning that he lived a life of sacrifice and self-denial.”

Gómez also argued that we cannot judge 18th-century behaviour by 21st-century standards – a form of historical relativism that the Serra critics find particularly galling. John Cornwell, a British journalist turned academic who has written extensively about the Vatican, including an acclaimed book about Pius XII, said the argument also clouded the important question of whether Serra was an appropriate exemplar for today’s faithful.

“For those who argue that we should not judge the values of the past by those of the present,” Cornwell told the Guardian, “one could, and should, object that it’s important to learn the lessons of history.”

To Native Americans like Valentin Lopez, the chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band based in Sacramento, those lessons are not complicated. Serra, in his view, was part of a colonial enterprise whose goal was the complete subjugation of California’s native peoples. The mission system he set up was based on coercion, punishment and indifference to Indian suffering, against which his expressions of piety were no more than window-dressing.

“It’s amazing to me this is even a debate,” Lopez told the Guardian. “There is no debate – it’s like debating the pros and cons of the genocide of the Jewish people in world war two. The only reason this is not treated as a black and white issue is because of the lies that the church and the state of California have perpetuated from the time of the missions.”

Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1884 bestselling novel Ramona set the tone for a mythologised history of the Missions, giving the impression Spanish colonialism had been an idyll for settlers and Native Americans alike and that the natives only suffered after the gringos began arriving. Even the most ardent Catholic historians now accept this is flat-out wrong.

A flurry of recent Serra scholarship, however, suggests the politics of the Spanish conquest were complicated. Missions were established with much greater success and lesser suffering in other parts of the American continent – particularly by the Jesuits. Serra’s mandate only arose because the Vatican temporarily disbanded the Jesuits in 1767, and many of the mistakes he and the Franciscans made were the result of inexperience, according to Professor Starr.

“The perspective of Franciscans and Dominicans of that era was: God will punish us for the way we treat the Indians, so we’ve got to protect them as some kind of atonement,” Starr told the Guardian. “Serra knew he couldn’t keep California a Franciscan mission protectorate forever. He hoped that by the time Spaniards came in large numbers, Native Americans would be educated and competent to deal with it. That was the dream, but the dream never came true.”

The biggest philosophical divide among serious historians is whether Serra’s initiative was worth undertaking in the first place. Catholic scholars – including Professor Starr – tend to take an indulgent view of the church’s evangelizing mission, while Native American advocates like Lopez view the imposition of Catholicism as a violation of the Indians’ longstanding spiritual traditions, just as the Spanish conquest disrupted and violated their way of life more generally.

The Vatican would like to believe that Serra and the missionaries were somehow separate from the Spanish colonial enterprise, and that the army’s abuses should not in any way be laid at Serra’s door. Pope Francis said in May that Serra was one of a generation of missionaries “who … defended the indigenous peoples against abuses by the colonisers”.

Most historians, however, dismiss that interpretation as fanciful. While it’s true that Serra was often at odds with military commanders in the region, he travelled to the New World at the behest and direction of the same Spanish crown in command of the army. He couldn’t be against the colonisers, because he was one himself.

“The church and the army were partners,” Lopez said. “Junípero Serra’s own handwriting details the cruelties. His policy was to enslave the Indians – he didn’t let them leave the missions. You can’t blame that on Spanish soldiers.”

Out of deference to the papal visit, the push to have Serra’s statue in Washington replaced with the late astronaut Sally Ride – championed by LGBT advocacy groups as well as fans of space exploration – has been deferred until after Francis is back in Rome. But the sponsors of the measure, including a Latino state senator from Los Angeles and the speaker of the state assembly, have vowed to reintroduce it thereafter – paving the way for yet more showdowns over Serra in the foreseeable future.

Hero or horror? Junipero Serra, priest behind Calif. missions, becomes a saint

Los Angeles (CNN)Andrew

Galvan knows the wound that lingers almost 250 years later, the one

that bears upon the genesis of the great American West.

The

British colonized the East, but here in California, the Spaniards

arrived with their armies and Catholic missionaries to take the West.

It

was Galvan's great-great-great-great-grandparents who in 1794 were

among the first Indians to be baptized in one of the state's iconic

missions whose architect was the pioneering and controversial priest

Junipero Serra.

Many Americans

may not know Serra's name, but here in California, the Spanish

missionary is as storied as the majestic coastline itself.

Serra initiated the building of the missions

that line California and remain a top tourist attraction. Every

fourth-grader here must learn the history of the 21 Spanish missions,

built between 1769 and 1823, some of them now National Historic

Landmarks. Serra built the first nine.

The

Vatican reveres Serra, too. In fact, Serra is deemed such a great

evangelist for the Catholic Church that Pope Francis officially declared

him a saint this week during his visit to the United States.

For

many Native Americans, Latinos and others, Serra was no saint, and his

canonization makes an old wound bleed again. But to those who champion

the missionaries' daring foray into the dominion of American Indians,

the sainthood heralds an apotheosis for the padre who brought the word

of Christ here.

"I wouldn't

say the announcement of the Holy Father to canonize Junipero Serra has

opened old wounds. It has provided an opportunity to remind many people,

including Indians, that there are wounds that require healing," said

Galvan, 60, of East Bay, California. "These wounds have been there. The

opportunity of canonization is an opportunity to heal these wounds."

That may or may not be.

Historic firsts on many levels

Francis,

the first Latin American pope, advanced the sainthood for Serra because

he was "one of the founding fathers of the United States" and a "special patron of the Hispanic people of the country," the Vatican says.

That

makes Serra's canonization a landmark moment for many Latinos, a people

born of the cataclysm when the Old and New Worlds met centuries ago.

After all, the first nonindigenous language spoken in America wasn't

English, but Spanish.

Serra became the first saint canonized on U.S. soil with Francis' declaration in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday.

The

setting made a not-so-subtle political point at a time when Congress

and presidential candidates remain ferociously deadlocked about

addressing an immigration flow so massive that Latinos are now the

largest U.S. minority, about a sixth of them without documentation.

"This is the big story: The first Hispanic Pope is coming to America to give us our first Hispanic saint. This is not a coincidence," Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles told the nation's religion writers at an August conference.

"But

this canonization is more than an ethnic event or a religious event.

The Pope is calling all of us in America to reflect on our history and

our nation's Hispanic and Catholic heritage and our legacy as a nation

of immigrants," Gomez said. "For me, this is probably the most important

dimension of the Pope's visit."

Francis also is the son of immigrants.

But

Serra left behind a dark legacy that inevitably occurs when colonizers

from the other side of the planet impose their will and religion upon an

indigenous people.

Contagion

and suffering decimated the native population several times over, and

now the descendants of those original tribes struggle with, if not

outright protest, sainthood for the missionary-in-chief of California.

Their own Catholicism deepens the conflict.

A period of brutality

For many, the wound is better healed by relegating Serra to the abyss of history.

To

them, the Franciscan friar from the island of Majorca represented yet

another front in Europe's imperial conquest of the native peoples and

lands of America.

"We're stunned and we're in disbelief," said Valentin Lopez, 63, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band located along Monterey Bay.

"We

believe saints are supposed to be people who followed in the life of

Jesus Christ and the words of Jesus Christ. There was no Jesus Christ

lifestyle at the missions," Lopez said, who has campaigned against

sainthood for Serra.

"The

mission period was brutal on our people," he said. "There can be no

doubt that Junipero Serra is personally responsible for destroying our

culture."

It's not easy

speaking against the church and the popular Pope because Lopez is

Catholic, as are many in his 600-member tribe, he said. In fact, he was

an altar boy for nine years in grade school.

"We

were raised not to say anything bad about the Catholic religion, but at

the same time, we can't stay quiet about this. It's like the altar boy

scandal. All the people who stayed quiet about the altar boy scandal,

how do they feel now?" Lopez said.

"It

seems like the church is doing all it can to separate Serra from the

atrocities and deaths and what happened to the Indians, but that does

not work," he said.

The life

of Serra remains as controversial as any of the so-called conquistadores

of Spain who ravaged their way through much of the Americas with

crosses and swords -- in pursuit of gold and silver while contending

they were servants of Christ and crown.

A history of disease and forced labor

Indeed, interpretations of Serra's legacy vary as much as the people telling it.

Consider what the official California school curriculum states bluntly:

"The

historical record of this era remains incomplete due to the relative

absence of native testimony, but it is clear that while missionaries

brought agriculture, the Spanish language and culture, and Christianity

to the native population, American Indians suffered in many California

missions.

"The death rate was

extremely high. Contributing factors included the hardships of forced

labor and, primarily, the introduction of diseases for which the native

population did not have immunity. Moreover, the imposition of forced

labor and highly structured living arrangements degraded individuals,

constrained families, circumscribed native culture, and negatively

impacted scores of communities."

Great evangelist of frontier West

Surely, Francis -- a native of Argentina and the first Jesuit pontiff -- knows the contentious legacy of the Spanish colonizers.

So

why did Francis grant Serra sainthood -- and even overlooked the

requirement of a second miracle by Serra that's typically needed for

sainthood? Under an extraordinary form of canonization, the pope

bypassed that requirement because a strong devotion among the faithful has long venerated Serra as saintly. Serra's first miracle was healing a nun of lupus.

"The

Pope is very concerned about the idea of evangelization," said Fr. Ken

Laverone, a church canon lawyer and a Franciscan in Sacramento who as

vice postulator is two degrees removed from the Vatican in Serra's

canonization process. Laverone's seventh-great-grandfather was among the

settlers who followed the missions, at San Jose, in 1774.

"He saw Serra as a prime example of evangelization in the western United States, in California, primarily," Laverone said.

Indeed,

Francis lays out a bold new vision for Catholicism, plagued by what he

called a "tomb psychology," and makes "New Evangelization" a centerpiece

of his papacy.

The Pope touched upon his pastoral standards in 2013:

"I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has

been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from

being confined and from clinging to its own security."

Though

Francis wasn't specifically referring to Serra, the intrepid Spaniard

does fit such a vision. Serra left behind a cushy academic job as a

university professor in Spain and became a missionary in modern Mexico,

with a vision to convert Indians on the entire North American coast to

Alaska. Serra died in 1784 at one of the California missions, in

present-day Carmel.

Laverone

asserted it's unfair to judge Serra in a 21st century context, but the

canon lawyer "wouldn't be surprised" if the Pope makes "a formal apology

and a plea of forgiveness from the native people" this week, as Francis

did in Bolivia this summer when he apologized for the "many grave sins" against South America's indigenous people during Spanish colonization there.

Serra led 'the genocide'

But

activists with the Mexica Movement such as Olin Tezcatlipoca call Serra

the leader of an atrocity. The movement is an indigenous right

education organization for people of Mexican, Central American and

Native American descent that advocates "total liberation from

Europeans."

"He planned the

genocide," said Tezcatlipoca, 55, a retired film editor in San

Bernardino who legally changed his name to an indigenous one because he

wanted "to do an ethnic correction with a name that reflects my true

heritage."

"The Pope is doing a continuation of genocide," Tezcatlipoca added.

Psychiatrist

Donna Schindler of Auburn, California, has worked with American Indians

and indigenous people as far away as New Zealand for most of her

31-year practice. She described the record of atrocity and abuse, retold

by Indian families today, as "historical trauma" or "intergenerational

trauma."

"It is the most

painful things imaginable to hear these stories," said Schindler, who

also works with Lopez' tribe. "The descendants have been suffering the

soul wound for 200 years."

Among

the ugly legacies for Indians is how their ancestors are buried in

unmarked graves in mission cemeteries -- and yet they are still charged

an admission fee of up $9 to enter a mission museum.

"This

is so over the top," Schindler said of Serra's sainthood. "You've hurt

these people already, and now we're going to reinjure them for no

particular reason.

"Why is

this so important? What do they think they're going to accomplish by

doing this?" said Schindler, a Catholic who stopped attending Mass this

year after plans for Serra's sainthood became official.

Historian's view: What really happened?

Serra's

fortunes rose after the Spanish crown expelled Jesuits from the empire,

and the Franciscans took over former Jesuit missions in Mexico, where

Serra had been based since 1750, said history professor Robert Senkewicz

of Santa Clara University, who with historian Rose Marie Beebe wrote a

recent book on Serra.

From

1769 until his death 15 years later, Serra worked in modern California

as part of the Spanish empire's expansion from Mexico City. Serra

founded nine missions from San Diego to San Francisco from age 55 until

his death at 70.

"The job of

the mission was to basically assimilate the native peoples, to make them

more Spanish. And part of making them more Spanish was basically making

them Catholics," Senkewicz said.

"It

wasn't that that the native peoples were dragged into the missions by

force, but they kind of had little choice in some senses because there

at least was some kind of food there," Senkewicz said.

Once in the missions, the Indians were baptized and couldn't leave without permission.

If

they didn't return on time, the priest would dispatch soldiers and

other mission Indians, "and they would forcibly bring people back to the

mission," Senkewicz said. "It's an odd sort of thing which is very

difficult to understand now because people were invited into the

mission.

"When they were

returned, the punishment was flogging, and the flogging was very severe

and it was very, very intense, and it was meant to be a painful

deterrent," the historian added. "And the flogging was pretty brutal at

times."

No documented evidence exists, however, that Serra himself flogged or used corporal punishment on the Indians, the Los Angeles Archdiocese says.

Serra

often distanced himself and his missions from the soldiers' garrisons,

and he "was constantly critiquing the military for its treatment of the

Native Americans," including rape of Indian women, Laverone added.

"He

didn't want them to be infected by the Spanish military way of

thinking," Laverone said. "There was a battle there. Am I in charge or

is the commander of the Spanish military?"

There was one thing Serra couldn't control: virulence.

The

Spaniards introduced disease that halved the Indian population from

310,000 to about 150,000 from the time of the missionaries' arrival in

1769 until California became a state in 1850, Senkewicz said.

As staggering as the toll was, the Indians learned skills, built the enduring missions and learned Christianity.

And Serra was the patrician father of it all.

"He

also was somebody who deep in his heart believed that he loved the

Indians," Senkewicz said. "He thought that they were like children, and

the missions were frankly paternalistic institutions, and Serra was

frankly paternalistic.

"A good father sometimes has to be stern and tough with his children," Senkewicz said.

Transformation of a mission archaeologist

Serra's impact on America speaks to the intersection of faith, identity, and origin.

Those themes exert profound power over people, and Ruben Mendoza is no exception.

An

archaeologist, Mendoza is director of the California missions

archaeological program at California State University, Monterey Bay,

where he is among the founding faculty.

But for much of his life, he despised the Spaniards and their conquest of native people.

After all, Mendoza's grandmother was a 4-foot-7-inch Yaqui Indian who lived in Mexico, where his family originates.

In fact, Mendoza, now 59, grew up reciting the Lord's Prayer in Nahuatl, an indigenous language of Mexico.

Born and raised Catholic in California's San Joaquin Valley, Mendoza condemned Spanish colonialism, which he called a "cancer."

"I had become very negative to anything related to the Spanish or the European," Mendoza said.

So he immersed himself in the culture of native people, which became his identity.

Then, life began to change when he worked an archaeological dig at a 16th century convent in Puebla, Mexico.

There he discovered something about himself.

Out of the rubble, he saw a mélange of artifacts of three peoples: European, Indian, and Mexican.

The relics piled together marked "the beginnings of an epiphany," he said.

"Until

1993, I was ultra-indigenous," Mendoza said. "I had ignored the

Hispanic dimension. There I was forced to reconcile both of those

things."

Later, in 2006, the diocese of Monterey asked Mendoza to assess one of the missions founded by Serra.

Mendoza

made another discovery: He found the original foundation of a chapel

used by Serra in 1772, making it the earliest formal Christian

architecture in California.

The

find left Mendoza thunderstruck. Serra's frontier evangelism among the

Indians left a profound impression. And now Mendoza was standing in the

remains of an area that once held the tabernacle.

"Suddenly,

all of my ancestors channeled me in this area. I'm a scientist, and I

now that sounds flaky, but it was so powerful, and I fell to my knees

and made the sign of the cross," Mendoza said.

"I

had an adversarial relationship with Serra which went unspoken up until

that moment," Mendoza said. "I am both of these traditions. Why do I

keep denigrating half of who I am in order to accommodate the

indigenous?"

Now when Mendoza is asked about Serra's canonization, Mendoza declares: "It's past due."

Though

he has been "attacked as a person of indigenous heritage working on the

missions," Mendoza welcomes how the Serra controversy "opens a dialogue

about Hispanics and the indigenous."

Galvan's story: the mission curator

Galvan, the fourth-great-grandson of the first mission Indians, has endured his share of vilifications, too.

What sets Galvan's story apart is his role in the California's missions.

He is the curator, or museum director, at Mission Dolores in San Francisco.

"I

am the only descendant of Indians who were missionized at any of the 21

California missions who is currently in a position of responsibility at

one of those missions. So it's a unique situation, and it's one that I

would hope in the next 20 or 30 years changes," Galvan said.

Galvan sees Serra's sainthood as an opportunity for Indians to leverage the church for changes at the missions.

He

would like to see free admission for visitors who are Native American,

the creation of a standard presentation on the Indian world before the

Spanish occupation, displays on which tribes built the mission, and an

acknowledgment of native peoples today.

"Somewhere

in the timeline, the Indians just disappear. Gone. They just don't

exist," Galvan said of the missions' educational features. "Most mission

museums do not even acknowledge that native people exist today."

In

fact, Mission Dolores doesn't even list the names of the 5,700 Indians

buried there between 1776 and 1834 -- except for two names.

They

are Galvan's fourth-great-grandparents, thanks to a grave marker

installed by Galvan. Galvan is urging the church to create a digital

projection screen of the remaining 5,698 names.

For

now, Galvan is encouraged by the missions and their bishops to consider

some of those proposals, though Galvan likens his efforts to "the dog

barking in the building." The Catholic Church now runs 19 of the 21

missions as active parishes.

"These

are the positive things that could happen. The pus is still oozing. Do

you want to put a poultice on it to make it better?" Galvan said,

referring to the enduring wound of Native Americans.

While a crusader about healing those injuries, Galvan nonetheless endorses the canonization of Serra.

In fact, he has urged sainthood for Serra for the past 37 years, working with the Franciscans' campaign.

"Everybody

... asks, Andy, how can you support the guy? I have to be able to sleep

at night. So I have answered that: I believe Junipero Serra was a very,

very good man in a very, very bad situation. And the bad situation is

what we call colonialism," Galvan said. "Junipero Serra is being

proclaimed a saint because he lived the life of a saint."

Galvan added a personal note: "He is the person who brings the Christian gospel to my ancestors in California."

With that conviction, Galvan will attend the Pope's official ceremony canonizing Serra in Washington this week.

There, he will take on another unique role.

"I will be the happiest Indian in the United States of America that day," he said of a St. Junipero Serra.

Updated 2253 GMT (0553 HKT) September 23, 2015 | Video Source: CN